One of the key factors in how we get-on in life is our ability to manage our mindset. Like training our bodies for an event, we can also train our minds to deal differently with life and work events. Without this training, we give up personal power and simply react to events around us.

In our volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous world (VUCA for short), we are often struck with a myriad of ‘triggers’ that can cause us to react. We can become defensive, aggressive, withdraw or become silent. Our ability to manage our mindset in the micro-moment between the trigger and our reaction ensures our own mind-care, as well as the collective mind-care of our workmates.

Often our emotions have automatic behaviours (both micro and macro) associated with them. When someone annoys us, we can roll our eyes, ignore them, pretend to be doing something else, or try to move on; all at a subconscious level. We display many automated behaviours; both helpful and unhelpful.

Hugely complex in it’s creation, the inner core of our brain creates our emotional reactions. Also known as the reptilian brain, its primitive responsive behaviour is designed to keep us safe.

Whereas the outer cortex of our brain is our “thinking” brain. Massively clever and complex, the boundaries of its potential are yet to be fully explored.

Unfortunately, the outer cortex of our brain is sometimes not activated during certain events, causing us to react, rather than respond. Putting it in colloquial terms; we can ‘flip our lid’.

When struck with a challenging situation that causes us to go into fear, we may come out fighting, belittle someone else, try to engage others into our behaviour, or retreat into silence and sulkiness. Our reptilian brain takes over. Fear is often a root-cause of this behaviour.

Being able to calm our mind when in this situation is not only vital for our personal mindcare, but also for the collective. This requires us to learn to manage our own mindset during these moments, as well as that of strategies in our collective mindset.

Humans are social beings, driven by a need to belong and feel valued. Psychological safety is the term used to describe the safety that we feel when we are together (Kahn, 1990 [ 1 ]). When in a group of people, we will screen others to evaluate if they will be rejected, ridiculed, mistreated, ignored or be insignificant. This drive to be social is often even more pronounced with people in powerful positions. Our evaluation may cause us to withdraw or move towards someone.

The thing is, however, this behaviour can be detrimental on a personal and collective level. It can hinder growth and diversity. It can cause us to move towards the more dominant person, or to back-away and become silent. This hinders our ability to share ideas, it also engenders a lack of commitment and accountability. At a collective level, it hinders shared responsibility.

A lack of psychological safety hinders personal and collective potential.

- It causes group-think, where we agree to the loudest or most powerful voice.

- It stifles creativity, replacing it with the status quo.

- It causes distrust.

- We avoid critical conversations, in return for keeping the peace at all costs.

- It masks the problems, sending behaviours ‘underground’.

- It causes anger, depression and people to “check-out”.

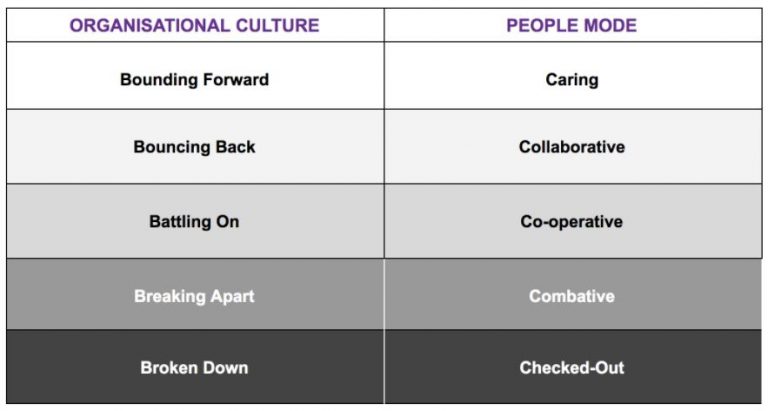

A lack of psychological safety can disintegrate organisational culture. The following table shows the relationship between Organisational Culture and People Mode. Where is your organisation or leadership situated?

Edmondson, 2012 [ 2 ] demonstrated the life and death importance of psychological safety in hospital cardiac teams. The research compared teams with high psychological safety (which tended to lower mortality rates) with those with low psychological safety (which tended to high mortality rates). Not only can high psychological safety literally save lives, individuals in organisations which have high internal trust experience 74% less stress, 106% more energy, 50% more productivity and 73% more engagement (Zak, 2017) [ 3 ].

We need to operate at two levels: the personal and collective, keeping an eye on the triggers within each.

My work alongside organisations supports them to create a “Culture of Care”, developing personal and collective ownership. Each person learns how to understand their emotional-social intelligence strengths and areas for development, and specific mind-care strategies to support them personally, and we collectively explore triggers, behaviours and strategies for maintaining a collective “Culture of Care”. This then lays the foundation for a high performing team. Check out what another incredible leader said about my Creating a Culture of Care programme:

What a privilege it has been to have had the opportunity for Mary-Anne to support our Kura’s journey of Creating a Culture of Care this year.

Mary-Anne’s high level of experience, knowledge, aroha and insight helped out staff to bring to the surface much needed conversations sharing vulnerability and demonstrate bravery.

Her dynamic style made everyone feel safe and comfortable throughout the entire process which enabled us to develop a shared understanding of the culture we wanted to make a reality.

Mary-Anne provided necessary tools that enabled much deeper conversations and clarity of the pathway we believed was right for our Kura.

Mary-Anne’s cultural connectedness and understanding of tikanga (appropriate to our setting) also enhanced our experience during the sessions we were able to complete.

The impact has been significant in such a short space of time, being able to repair as well as forge a positive shared pathway forward has been our greatest win. Every staff member has been left with the feeling of wanting more and can’t wait to further develop the Culture of Care plan we’ve begun.

Thank you Mary-Anne for providing us with the platform we so needed to enable this to happen. We are excited about what our future holds.

Sunny West, Principal, Kihikihi School

So, if this resonated with you, then feel free to drop me a line and let me know what you are experiencing and how you would like it to be different.

Ngā mihi nui

Mary-Anne 🙂

References:

Kahn, W., 1990. Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), pp.692-724.

Edmondson, A., 2012. Teaming. San Francisco, Calif.: Jossey-Bass.

Zak, P., 2017. The Neuroscience of Trust. Harvard Business Review, [online] (January-February 2017). Available at: https://hbr.org/2017/01/the-neuroscience-of-trust